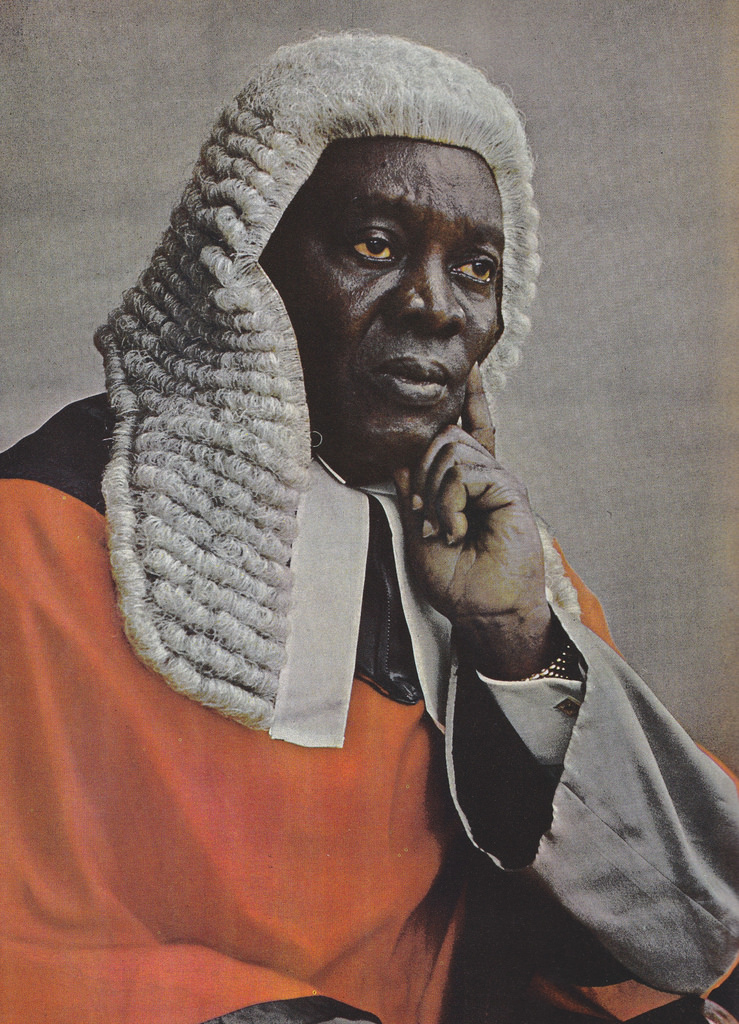

Justices series : Sir Arku Korsah, his work and impact on Ghana’s justice system

The man represented many things – from being a legislator to a judge, serving as Chairman of various Commissions of Inquiry, and then an intellectual who was one of the founding members of the Ghana Academy of Arts & Sciences.

History as is told, often times begins with a first individual – in Ghana’s case, the first President was Kwame Nkrumah, the first Speaker of Parliament was Sir Emmanuel Charles Quist and for her judiciary, Sir Justice Kobina Arku Korsah was the first Ghanaian Chief Justice.

To reflect the new trajectory Ghana was being ushered into, and since it was nearing independence and in sync with the name change from Gold Coast to Ghana, Sir Justice Arku Korsah can very well be referred to as Ghana’s first Chief Justice.

The man represented many things – from being a legislator to a judge, serving as Chairman of various Commissions of Inquiry, and then an intellectual who was one of the founding members of the Ghana Academy of Arts & Sciences.

His appointment to serve as Chief Justice began in 1956, after the death of the colonial Chief Justice, Sir Mark Wilson. He was reappointed by Nkrumah, but was sacked in 1963 after the Kulungugu bombing trial which he presided over.

This article fills in on his work as Chief Justice, his contribution to constitutional development and the legal landscape, as well as the notable events at the time of his tenure.

As Ghana's First Chief Justice

Passing through the hierarchy before his elevation as Chief Justice, Sir Justice Arku Korsah served as Pusine Judge in 1945, the then common law reference to a judge of a lesser rank. He mostly sat on commercial, land and matrimonial (customary) cases. The following year, he was promoted to preside over cases at the West African Court of Appeal (WACA).

And perhaps one of the earliest criticisms against him was from scholars asserting that he had a strict adherence to colonial interpretation of the law. The case in question was Abude and ors. v. Nii Adjei Onano and ors, where citing native law, he held that the head of the family was immune to accountability from other members of the family.

As Chief Justice to a new Ghana, there will obviously be a lot to establish. Korsah started in that regard by adding more court infrastructure to the existing ones.

Like Nkrumah, he was one of those Africans with an Africanisation drive, which led him to appoint more Africans to the lower and superior courts. Justices Nii Amaa Ollenu and Kofi Adumua Bossman were among the judges appointed by Korsah to the courts in 1956. He also recommended Edward Akufo-Addo to Nkrumah to succeed Geoffrey Bing as Attorney-General, but when Nkrumah opposed the idea, he convinced him to appoint Akufo-Addo to the Supreme Court instead.

Following Ghana’s independence, he ensured the country exited WACA, and created the first Court of Appeal, known as the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council as the final Court of Appeal. And in December 1957, one of his judgments in the Court of Appeal case of Quagraine v Davies was overruled by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

Of the very defining structures of the legal profession, Korsah was again involved in their establishment. One of those was the General Legal Council (GLC), where together with Edward Akufo Addo and Geoffrey Bing, they established the GLC under the Legal Practitioners' Act, 1958, and subsequently the Ghana School of Law. Next was the establishment of the Ghana Law Report (GLR) and an attempt to make J. B. Danquah the first editor.

Most of the cases Sir Justice Arku Korsah presided over were commercial cases and common law cases of politico constitutional interest. They were generally considered as cases with strong political undertones and as such made the then Chief Justice an easy target for opposition members' propaganda.

Re-Akoto and Seven Others Trial

The 1961 Re-Akoto and seven others trial was one of the famous cases during Korsah’s time as Chief Justice.

Baffour Osei Akoto, a Senior Linguist to the Asantehene, Peter Alex Danso, Osei Assibey Mensah, Nana Antwi Boasiako, Joseph Kojo Antwi-Kusi, Benjamin Kwaku Owusu, Andrew Kofi (mistakenly written as ‘Kojo’) Edusei and Halidu Kramo were arrested and detained under the Preventive Detention Act, 1958.

Through their lawyer J. B. Danquah, they brought a case of Habeas corpus and Subjiciendum before the High Court. The case was dismissed, and they appealed against the decision of the High Court at the Supreme Court.

At the Supreme Court, they argued that the PDA was in excess of the powers conferred on Parliament by the Constitution of Ghana, specifically article 13(1) or it is contrary to the solemn declaration of fundamental principles made by the President on the assumption of office. And that the PDA not having been passed under a declaration of emergency is in violation of the Constitution, 1960.

Mr. Danquah also argued that the PDA rubbished the Criminal Procedure Code, which states that all offences, “shall be inquired into, tried and otherwise dealt with in accordance with the provisions of the Code.” He, therefore, sought to ask the Court to assume the powers of judicial review, as the United States Supreme Court would have, and strike out the PDA.

However, the Supreme Court, with Korsah presiding, indicated that article 13(1) of the Constitution, 1960, was a non-binding declaration principles by the President. The interpretation by the Court was that article 13 (1) was similar to the Coronation Oath of the Queen of England, and therefore it did not create legal obligations enforceable in a court of law.

The Court also held that the Criminal Procedure Code was valid for actual crimes committed, while the PDA had in mind crimes yet to be committed in the future.

Following the ruling, Korsah received sharp criticism from legal scholars like Professor Samuel Otu Gyandoh, Academics and even Justices of the Supreme Court, and also the International Commission of Jurists (ICJ).

“By the Supreme Court`s interpretation, the Court declared itself as being impotent to interfere or examine the propriety and legality or otherwise of a citizen's detention by the State,” Professor Bimpong-Buta said in his book, ‘The Role of Supreme Court.’

Furthermore, in support of the unanimous decision in the case of New Patriotic Party v Inspector-General of Police, Charles Hayfron-Benjamin JSC said that the decision “undermined” the very fabric of the Constitution, 1960 and thus pushed aside certain principles and fundamental human and civil rights which has become the “bulwark” of the Constitution, 1992.

Also in his opinion in the case of Amidu v President Kufuor, Kpegah JSC said that;

“Every student of the Constitutional Law of Ghana might have felt, after reading the celebrated case of In re Akoto that if the decision had gone the other way, the political and constitutional development of Ghana would have been different. ‘Different’ in the sense that respect for individual rights and the rule of law might well have been entrenched in our land, and we who now occupy this court would have had a well-beaten path before us to tread on in the discharge of our onerous responsibilities imposed upon us by the 1992 Constitution.”

The Re-Akoto and seven others' trial, is noted as the case that set grounds for the future formulation of fundamental human rights enshrined in chapter 5 of the 1992 Constitution.

The Kulungugu Bombing Trial

Two years after the Re-Akoto case, Korsah presided over another trial, the Kulungugu bombing trial of 1963 – the case that led to his demotion as Chief Justice.

The incident was a failed assassination attempt on Nkrumah, and three high-profile members of the CPP (Tawia Adamafio, Minister for Information and Minister responsible for the President’s Office, Ako Adjei, Foreign Minister, and H. H. Cofie Crabbe, Executive Secretary of the CPP) and two opposition members (Joseph Yaw Manu, store-keeper, and Robert Benjamin Otchere, former Member of Parliament) were said to have conspired with Obetsebi-Lamptey to overthrow the government.

A special court was set up under the Criminal Procedure (Amendment) Act, 1961 to try the treason case.

Korsah along with two other Supreme Court justices – Edward Akufo-Addo and W. B. Van Lare found the two opposition members guilty, while Adamafio, Adjei, and Crabbe were freed because the court held the state’s evidence against them was very weak.

According to the Chief Justice even though the three were suspicious, it wasn’t enough to convict a person based only on suspicion.

What followed was a swathe of criticism and protest against the court’s decision, Korsah himself, and the judiciary. After Nkrumah revoked his appointment as Chief Justice and demoted him to become one of the ordinary judges of the Supreme Court. Korsah tendered in his resignation, and so did the other justices that sat on the trial.

Regardless of the criticism against Korsah, critics asserted that he was a brilliant judge, whose many judgments served as precedents.