Female Afghan judges hunted by the murderers they convicted

“I look at my young son and I don’t know how to explain to him why he can’t talk to other children or play out in the hall. He’s already traumatised.

They were the trailblazers of women’s rights in Afghanistan. They were the staunch defenders of the law, seeking justice for their country’s most marginalised. But now, more than 220 female Afghan judges are in hiding due to fear of retribution under Taliban rule. Six former female judges spoke to the BBC from secret locations across Afghanistan. All of their names have been changed for their safety.

Throughout her career as a judge, Masooma has convicted hundreds of men for violence against women, including rape, murder and torture.

But just days after the Taliban took control of her city and thousands of convicted criminals were released from prison, the death threats began.

Text messages, voice notes and unknown numbers began bombarding her phone.

“It was midnight when we heard the Taliban had freed all the prisoners from jail,” says Masooma.

“Immediately we fled. We left our home and everything behind.’

In the past 20 years, 270 women have sat as judges in Afghanistan. As some of the most powerful and prominent women in the country, they are known public figures.

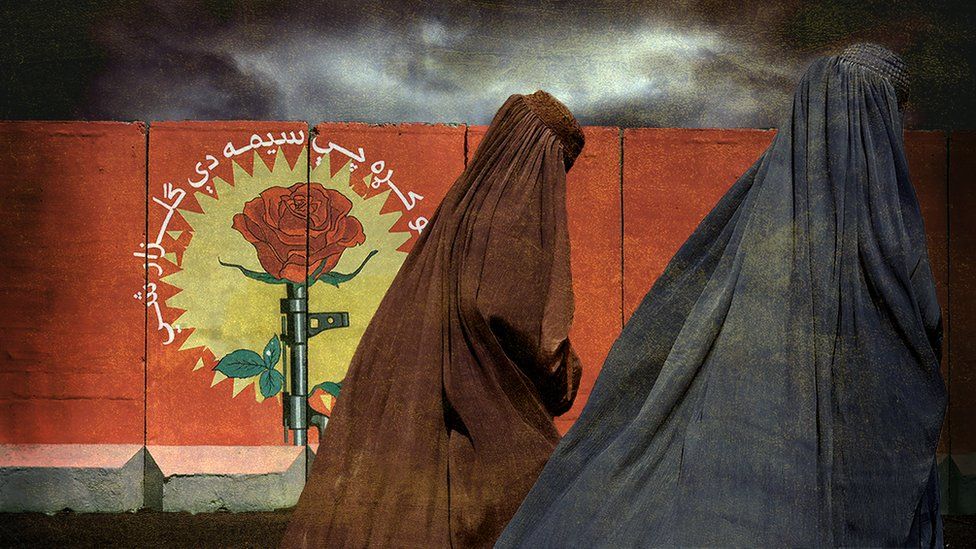

“Travelling by car out of the city, I wore a burka, so no-one would recognise me. Fortunately, we made it past all the Taliban checkpoints.”

Shortly after they left, her neighbours texted her to say several members of the Taliban had arrived at her old house.

Masooma says that as soon as they described the men, she knew who was looking for her.

Several months ago, prior to the Taliban takeover, Masooma was ruling over a case investigating a member of the group for brutally murdering his wife.

Upon finding him guilty, Masooma sentenced the man to 20 years in prison.

“I can still see the image of that young woman in my mind. It was a brutal crime,” says Masooma.

“After the case was over, the criminal approached me and said: ‘When I get out of prison, I will do to you what I did to my wife.’

“At the time I didn’t take him seriously. But since the Taliban took power, he has called me many times and said he has taken all of my information from the court offices.

“He told me: ‘I will find you and have my revenge.'”

At least 220 former female judges are known to currently be in hiding across Afghanistan, a BBC investigation has found.

Speaking to six former judges from different provinces, their testimonies of the past five weeks were almost identical.

All have received death threats from members of the Taliban whom they previously committed to prison. Four named specific men whom they sentenced for murdering their wives.

All have changed their phone number at least once due to receiving death threats.

They are all currently living in hiding, moving locations every few days.

They all also said their former homes had been visited by members of the Taliban. Their neighbours and friends reported being questioned as to their whereabouts.

In response to the accusations, secretary to the Taliban spokesman Bilal Karimi told the BBC: “Female judges should live like any other family without fear. No-one should threaten them. Our special military units are obliged to investigate such complaints and act if there is a violation.”

He also repeated the Taliban’s promise of a “general amnesty” for all former government workers across Afghanistan: “Our general amnesty is sincere. But if some wish to file a case to leave the country, our request is that they do not do this and they stay in their country.”

During the mass release of prisoners, many criminals not associated with the Taliban were also released.

With regards to the security of female judges, Mr Karimi also said:

“In the case of drug traffickers, mafia members, our intention is to destroy them. Our action against them will be serious.”

As highly educated women, these judges were previously the main breadwinner for their families. But now, with their salaries stopped and their bank accounts frozen, they have all been reduced to living off hand-outs from their relatives.

For more than three decades, Judge Sanaa investigated cases of violence against women and children.

She says the majority of her cases involved convicting members of the Taliban as well as militant group Isis.

“I have received more than 20 threatening phone calls from former inmates who have now been released.”

She is currently in hiding with more than a dozen family members.

Only once has one of her male relatives returned to their former family home. But as he was packing some clothes, the Taliban arrived at the house in several cars full of armed men, led by a commander.

“I opened the door. They asked me whether this was the judge’s house,” he says. “When I said I didn’t know where she was, they threw me on the stairs. One of them hit me with the butt of his gun and started beating me. My nose and mouth were covered in blood.”

After the armed men left, Sanaa’s relative took himself to hospital.

“I told another relative we must keep changing the house where my sister is staying. There is no other way out now. We can’t escape to any other country, even Pakistan.”

Fighting for women’s rights

For decades, Afghanistan has continued to rank as one of the hardest countries in the world. According to Human Rights Watch, an estimated 87% of women and girls will experience abuse during their lifetime.

But this community of judges, by working to uphold the country’s former laws which aimed to support women, have helped to advocate for the idea that violence against women and girls is a punishable criminal offence.

This includes charging individuals in cases of rape, torture, forced marriage, as well as in cases where women were prohibited from owning property or going to work or school.

As some of the most prominent female public figures in their country, all six say they have faced harassment throughout their careers, long before the Taliban took full control.

“I wanted to serve my country, that’s why I became a judge,” says Asma, speaking from a safe house.

“In the family affairs court, I dealt mostly with cases involving women who wanted a divorce or separation from members of the Taliban.

“This posed a real threat to us. Once, the Taliban even launched rockets at the court.

“We also lost one of our best friends and judges. She disappeared on her way home from work. Only later was her body discovered.”

No-one was ever charged for the disappeared judge’s murder. At the time, local Taliban leaders denied any involvement.

How draconian Afghanistan’s new leadership will be regarding women’s rights is still yet to fully unfold. But so far the outlook is grim.

An all-male acting cabinet with no appointment to oversee women’s affairs has already been announced, while in schools, the education ministry has ordered male teachers and pupils go back to work, but not female staff or students.

On behalf of the Taliban, Mr Karimi said he could not yet comment on whether there would be roles for female judges in the future: “The working conditions and opportunities for women are still being discussed.”

So far, more than 100,000 people have been evacuated from the country.

All six judges say they are currently looking for a way out – but not only do they lack access to funds, they say not all members of their immediate families have passports.

Former Afghan judge Marzia Babakarkhail, who now lives in the UK, has been advocating for the urgent evacuation of all former female judges.

She says it’s important not to forget those living in Afghanistan’s most rural provinces far from the country’s capital, Kabul.

“It breaks my heart when I receive a call from one of the judges from the villages saying: ‘Marzia, what should we do? Where should we go? We will be in our graves soon.’

“There is still some access to the media and the internet in Kabul. The judges there still have some voice, but in the rural provinces, they have nothing.”

“Many of these judges don’t have a passport or the correct paperwork to apply to leave. But they cannot be forgotten. They are also in grave danger.”

Several countries, including New Zealand and the United Kingdom, have said they will offer some support. But when this help will arrive or how many judges it will include is yet to be confirmed.

Judge Masooma says she fears such promises of help will not arrive in time.

“Sometimes I think, what is our crime? Being educated? Trying to help women and punish criminals?

“I love my country. But now I am a prisoner. We have no money. We cannot leave the house.

“I look at my young son and I don’t know how to explain to him why he can’t talk to other children or play out in the hall. He’s already traumatised.

“I can only pray for the day when we will be free again.”